#60 - Le style cest l'homme!

Last updated: Oct 14, 2023

I struggled a lot in the past two years with the idea of having an investing style.

Style is a vague word. Some people use “philosophy” or “principles” interchangeably.

Why is it important to have a style? Should an investor have a well-defined style, if they are to be successful?

I fought against the idea, at first. It seemed to me that having a style is way too limiting and would preclude me from taking advantage of many opportunities because they didn’t fit whatever arbitrary style I would have chosen.

But I feel like I might have changed my mind. Slowly, imperceptibly, and almost reluctantly.

What if we shouldn’t choose a style (based on expected performance) but instead find our own style?

What I mean is: maybe our style exists already; it’s out there. And our job is to find it, to recognize it.

Maybe the purpose of investing (and life) is to understand who we are, have our actions be aligned with who we are, and unlock our flywheel of personal growth.

Viewed this way, all of sudden, I see the appeal, not of having a style, but of finding my own.

Below is a video clip of Chuck Akre talking about his set of investment principles (known as the “three-legged stool”).

He looks for three things:

-

a quality business, defined as a business with a high return on capital, and he wants to understand the essence of that business or why they’re able to generate such high returns

-

quality management, defined as management with high integrity and a proven track record, and that treats shareholders as partners

-

room for reinvestment, to allow the compounding to happen

I’m gonna link directly to the conclusion of his talk, which is the section that resonated with me the most. He’s basically saying: “Find your own style, find what works well for you, then do that - and only that”.

I’m reminded of the late King of Morocco, Hassan 2. When asked about how he thinks about his succession, he says (in French): “Le style, c’est l’homme”. Style is everything. I think what he meant is that whoever his succesor is, they should strive to find their own style and go with it.

Here’s another fund manager whose investment style I admire: Terry Smith

Terry only invests in quality businesses, which he defines as such:

Notice the overlap with Chuck Akre? Hopefully, it means that I’m consistent and that I may have found the building blocks of my own style.

When it comes to investors I admire, Chris Mayer is also one of my favorites. Here’s a quote from his blog:

Again, high return on capital - but with a strong emphasis on competitive advantage.

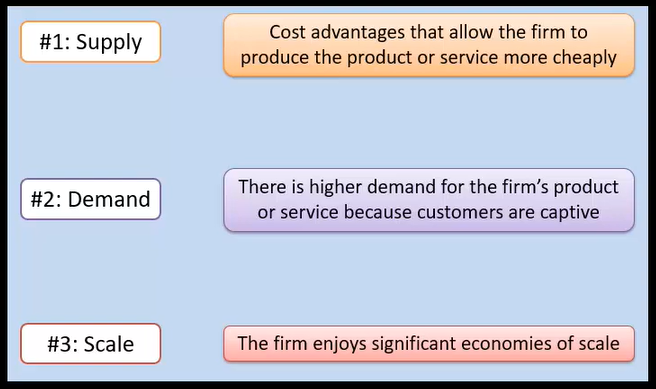

Bruce Greenwald’s has written a fair deal about competitive advantages:

The screenshot above was taken from the following clip, which summarizes well the best chapter (in my opinion) of Greenwald’s book, Competition Demystified.

If you don’t mind listening to Greenwald’s nasal voice, this one is a pretty good clip on what makes a good business (i.e. a business that generates high returns on capital for long periods of time, as per Smith and Mayer’s definition):

I can rarely remember fictional character names. But I remember the name of Hari Seldon, from Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series.

In the book series, Hari Seldon developed “an algorithmic science that allowed him to predict the future in probabilistic terms. Based on his psychohistory he is able to predict the eventual fall of the Galactic Empire”.

I remember finding this idea fascinating, and not all that crazy. Based on a combination of irreversible secular trends, the mathematician was able to derive a probabilistically almost-inevitable end state of the system, whatever the actions of any individual or groups of individuals.

It’s as if there was a structural shift happening that nothing can stop - and everything else is just random noise.

It reminds me of this tweet describing how Buffet became one of $AAPL’s biggest shareholders:

Buffet recognized an unstoppable trend - one that, ironically enough, Bruce Greenwald missed, because he didn’t understand how Apple captured their customers’ life and soul through that little electronic gadget!

On top of it, the stock was dirt cheap; so he went all-in.

That’s what a great investment opportunity looks like. One where the end state is probabilistically preprogrammed (everything else is noise), and everybody (i.e. the market) is blind to it.

I know, I’m over-simplifying. Nothing is ever certain, in investments and in general.

I’ve just started reading Chris Mayer’s book “How do you know?” and I’m enjoying it tremendously.

In chapter 2, he shares one of the basic frameworks of general semantics. I don’t want to get lost in the details, but the idea is that out of an infinite number of events happening in real life, we only perceive a few objects (abstractions), on which we slap some labels, from which we derive inferences.

These inferences in turn shape which events we will pay attention to in the future.

It’s a way to depict not only how much resolution we lose between reality and our “map” of it, but also how much of reality we simply are not aware of.

I’ve recently become aware of how little I know about the companies I follow. It occurs to me that pretty much everyone knows very little about the companies they invest in.

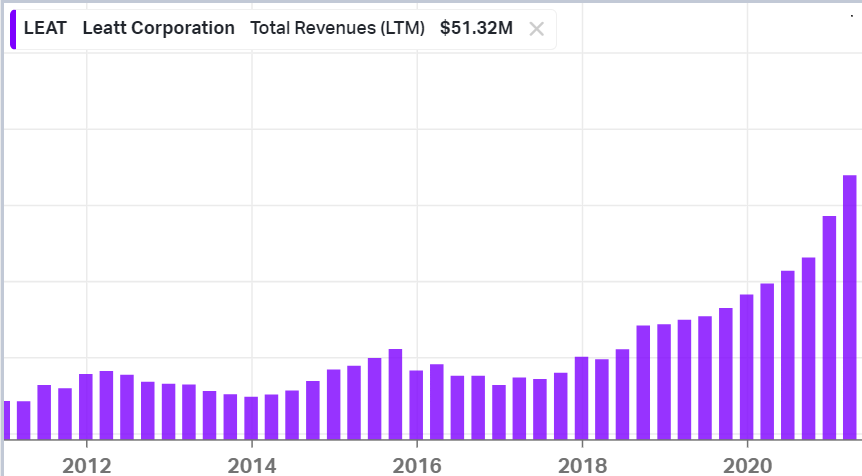

Take $LEAT as an example. This is a company that designs and sells personal protective equipment for motorsports.

The company has been highly successful in growing its revenue by broadening its product offering and using a DTC (online) channel:

As a result, it has attracted a bit of a following on fintwit.

So I asked the question: why has this company been successful? What is its competitive advantage? And most importantly, how can we predict its future success, with a high degree of certainty?

The answers I got back were disappointing, to say the least.

In essence, it’s a small and innovative company that has been executing well and still has a lot of room for growth.

Notice how shallow this description is. I’m sure there must be a lot of companies that could fit it.

Nothing in this description tells me what the end state is and why it’s inevitable.

Again, I know that certainties don’t exist. But that’s my point. There are so many uncertainties, so many variables, that if we don’t start from a place of ultra-high conviction driven by a simple yet profound thesis…we don’t stand a chance.

Leatt might be a great success, or not. I can’t tell. I can’t “see it” and it feels like a gamble.

Joel Greenblatt said it best:

When you recognize that you have this other way to look, and that makes total sense to you, and all the pieces fit when you look at it that way, those are the great opportunities.

There’s another reason why we need a strong, simple yet profound thesis.

It’s because if we don’t, and if we merely follow other people into an investment idea, we will be at the mercy of the wind - and chances are, we will be shaken out.

Here’s Warren Buffet emphasizing this point.

Very imp. advice by @Warrenbuffet

— Komal Sharma (@Komal_Stocks) June 26, 2022

And follow @KomalSecurities

For such quality content.#Komalsecurities #StockMarket. pic.twitter.com/crxfqobFn7

I saved the audio file here in case the tweet goes down at some point.

Another one of my favorite investors is Tobias Carlisle, founder of The Acquirers podcast and The Value: After Hours podcast.

As much as I like him as a person (he seems very intelligent and honest), he has a different approach. His is a statistical one, where he buys a basket of stocks with a low EV/EBIT multiple (so-called the acquirer’s multiple).

Joel Greenblatt had championed a similar approach, which used two criteria instead of one, the second being a high ROIC.

But what Tobias found out is that this criterion was actually hurting the performance of Greenblatt’s magic formula, so he got rid of it.

He explained the reason behind this underperformance by using the concept of reversion to the mean. Intuitively, when you choose a lot of stocks randomly with the condition that they have a high ROIC, a lot of them are bound to meet this condition for reasons that are extrinsic to the company, and not intrinsic.

Most of the time, the reason will be a lack of competition, often due to the sector being momentarily out of favor. But as soon as competitors notice the high ROIC, they jump in the fray. The higher the competition, the lower the returns.

When returns get low enough, a bunch of the competitors die out, and we start the cycle anew.

That’s the gist of the return to the mean concept. High returns do not beget high returns. Instead, high returns are more likely to be followed by low returns. Therefore, it’s not useful to filter on that criterion.

So here’s what I don’t like about this approach.

Reversion to the mean is not a core principle or an axiom. It is a consequence of something.

That something is the combination of two things: 1) random (non-Markov) processes and 2) the existence of a limit. I’ll get back to this later but first, let me just clarify what we typically mean by reversion to the mean.

The typical example is that of a father who is much taller than the average, and who has a son. This son is likely to be shorter than his father. And vice-versa, offspring of shorter parents tend to be taller than them.

Why is that the case? The main reason is that there is a limit to how tall we humans can get. For every father, the distribution of the height of their children has a mode equal to the height of the father.

If the father has an average height, the distribution will be a normal distribution, symmetric around the mode, and their children will be as likely to be taller or shorter than them.

But if the father is particularly tall, that distribution will be skewed, due to the hard limit on how tall a human being can be.

That’s the fundamental reason why reversion to the mean happens.

The second reason is randomness, more specifically non-Markov randomness.

A Markov process is one where the probability distribution of the current state depends on earlier values. A non-Markov process is one where the current probability distribution is independent of earlier values.

The example above is a Markov process. Because of genetics, the height of my children, as a random variable, does depend on my own. And so if man A is much taller than man B, it is reasonable to expect that the decendents of A will on average be taller than the descendants of B.

Imagine instead that human children, instead of being born out of their mothers’ wombs, were delivered to their parents by some kind of bird, and that genes were not passed on from generation to generation.

Then not only would we observe a reversion to the mean from one generation to the next, but we would also observe it across generations. In other words, one generation’s height would tell us nothing about the next one’s.

Going back to the investment realm, roughly speaking, the limit is the TAM divided by how many competitors can compete economically in a given space.

This limit always exists, but how far away it is will depend on the structure of the sector.

The randomness portion is more important and brings us back to the most important concept we’ve talked about so far: competitive advantages.

A company can have a high ROIC for a period of time just by luck, because of a specific and ephemeral set of external circumstances.

Or it can have such a high ROIC because it is doing something right, in a way that competitors are not able or interested in replicating.

Of course, the second category is much more scarce than the first one. That is why Tobias’ approach is consistent and should work, statistically speaking.

But, if you’re able to understand WHY a company is having success, and if you’re able to predict that this success will last and NOT revert to the mean…then you don’t need to diversify and buy a basket of stocks.

You just need to buy the one that has a strong competitive advantage.

Notice that I have talked about “competitive advantages” and not about moats.

I don’t really like moats as a metaphor. They feel too static for my liking, especially in the world we live in today.

I’ve also been reading Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, a book that was recommended by Yen Liow (who has since closed down his fund).

The book describes how Genghis Khan’s army crushed every opposing army, despite all their fortifications and moats because (and this is my interpretation) the Mongol army had a fundamental and structural competitive advantage, that could not be easily copied.

Funny enough, (again, as I understood it) the advantage they had is that they were LESS advanced than surrounding people, who were living much more comfortable sedentary lives. The Mongols were nomads, and hunters, used to having to “kill what they eat”.

War was not a matter of prestige or honor for them. It was all about killing the opponent while maximizing the odds of success. In fact, they abhorred close combat. They instead perfected the use of bows and arrows while riding their horse, and they were extremely mobile.

Ironically enough, their lack of technological prowess also turned out to be an advantage, as they were open to any ideas that could give them an edge in war, and they ended up absorbing the best technologies from the people they conquered on their path.

The Mongols never lost a fight on land. Because they never picked a fight that was even remotely fair. Every fight they fought was one where the odds were massively tilted in their favor, one way or another.

So Gengis Khan’s Mongols didn’t have a moat. Their opponents had moats. But the Mongols had structural competitive advantages, and not a single army could resist them.

I also don’t want to look for static moats in the investment world. I’d much rather find structural competitive advantages that will unfold into winning territories, i.e. market share.

The preceding sections make it sound like I have this investing all figured out.

I don’t.

As I’m reading Chapter 2 of “How do you know?”, Chris Mayer mentions Jim Collins’ book: “Good to Great”.

I remember that the book had made quite an impression on me when I first read it. Collins seemed to have cracked the code.

And yet it turns out, that if you invested in Collins’ select list of “great companies”, your returns in the following 5 years would have been worse than random.

Sure, 5 years is not a super long timeframe, but still…

This wasn’t Jim Collins’ first attempt either, and he wasn’t the only one to have tried to distill down the characteristics of great companies.

If he and his mini-army of analysts were dead wrong after thousands of hours of research, what chance do I stand?

Going back to my example with the Mongol army. I made it sound like it was evident that they would defeat their enemies.

But I cheated - I knew what had happened historically. If you had shown and described the armies to me and asked me to bet all my money on the winner, there’s no way in hell I would have bet on the Mongols with their little bows versus the heavy infantry of the Europeans, especially outnumbered two or three-to-one as they were.

And it doesn’t matter how much information you gave me. In fact, the more details I would have had, the more obvious it would have seemed to me that the Europeans would easily defeat the Mongols. That’s what they thought too! That’s what every new army the Mongols faced thought.

There’s only one thing that would have made me reconsider.

That’s if I had seen a track record of the Mongols, including previous battles where they decimated bigger and better-equiped armies. That could have caused me to at least ask: “Home come?”

I recently watched an exceptional stock pitch from a talented young fund manager named Guy Gottfried, where he stresses the importance of the management’s track record. It’s worth a watch:

He’s also very adamant about having an edge, which oftentimes comes from looking at things that are underfollowed or out-of-favor. He says: “If 10,000 other investors are already looking at a deal, why would I believe that it’s a great one?”

Checking the track record of a company and its management, and making sure that they accomplished what they said they would do, is critical.

Back to our topic though: the investing game. It’s not an easy one. It’s only easy when you already know the answer, looking back.

Put a chess Grand Master in front of a chess board where there is one and only one winning move that is hard to find (but don’t tell him that), and he might not find it, especially under time pressure.

But tell him that there’s a winning move, and he will somehow see it almost every time.

When the “what” is known, it’s much easier to figure out the “how”.

I understand Tobias Carlisle’s approach. It acknowledges the limitation of our knowledge and uses the law of large numbers to still achieve a good performance. It’s a humble and intelligent approach.

It’s not easy to figure out which companies will win.

This is why we must insist on only hitting the easiest pitches, and why we must also insist on having a margin of safety, in case we’re wrong, usually in the form of a discounted price.

In closing, we want to buy:

- quality businesses that have a competitive advantage

- that earn high returns on tangible capital and can reinvest a high % of their earnings

- that are easy for us to understand and forecast

- whose management has a solid track record we can check and a shareholder-friendly mindset

- at an attractive price

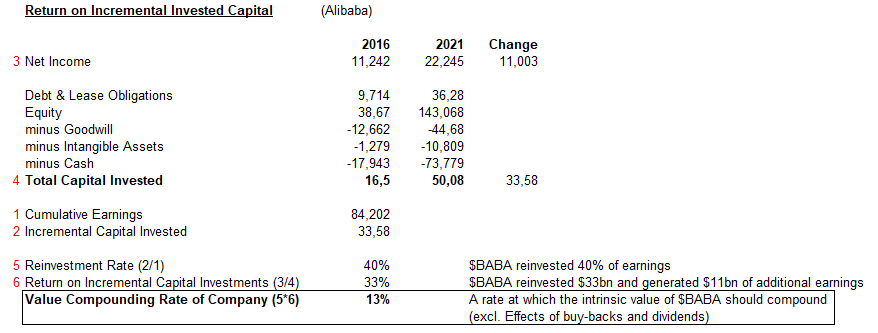

On the second point, I recently stumbled on this very nice illustration with $BABA:

Once we find and buy such businesses, we want to have to wisdom to sit on our asses and do nothing for very, very long periods of time.

Let us remember that we are in the game of making money.

We are not in the game of being right, proving how smart we are. It’s not a popularity contest.

The only question that matters is: how will we be consistently making money?

Disqus comments are disabled.